|

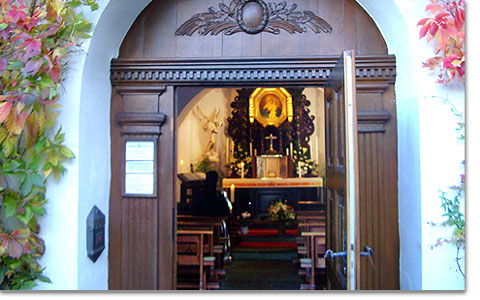

| Donde todos entienden todo... Where all understand... Wo alle alles und einander vestehen... Foto: POS Fischer © 2007 |

SOUTH AFRICA, Sarah-Leah Pimentl. I was moved to exercise my grey matter after reading Simon Donelly’s article "The mystery of how I can know Schoenstatt: speaking and living in German (or English, or...)." His reflection touched more than a few chords. Like him, I’m fascinated by the interaction and relationships that languages have with one another. In addition to this, I find myself two weeks from pursuing a degree in Translation and am debating whether such a career is indeed truly possible. Perhaps more than all that, I miss the occasional conversations that Simon and I used to have after morning Mass on a Saturday at our Shrine in Johannesburg, South Africa. They were always highly interesting and kept me thinking and asking questions for weeks afterwards!

Like Simon, I find Schoenstatt to be a mystery that can be "translated" into my home language, my culture, the social fabric of my country, but at the same time defies translation.

A common ground

It must be a very different experience to be part of the Schoenstatt Family living in Germany and speaking German. To begin with, it is so much easier to visit the Urheiligtum (‘Original’ Shrine), to learn about and live Schoenstatt’s spirituality straight from the mouth of the Founder – so to speak – and to have a better understanding of the post-modern and increasingly nihilistic world that Fr. Kentenich witnessed and physically experienced (especially in the throes of WWI, the rise of Nazi Germany and the loss of hope in Dachau). For those of us who live outside of Germany, who speak languages other than German, and for whom European history of the first half of the twentieth century is little more than textbook knowledge, it takes a powerful leap of the imagination to even begin to conceive of the world that Fr. Kentenich saw disintegrating before his eyes, and, guided by the Holy Spirit and Our Blessed Mother, felt compelled to educate individuals to become new people for a new society.

Despite the often alienable differences between Fr. Kentenich’s world and our own, there are two constants that unite each member of the Schoenstatt Family under a common experience: the Shrine and our Covenant of Love with our Mother. Both of these operate in as well as outside of the realm of language. The experience of the Shrine is one of grace. Grace does not need language to make itself felt. When we were being catechised as children, grace was explained to us in words and in so doing, grace becomes somewhat rationalized. But no one who has ever experienced the gift of grace can call it a rational experience. It is a feeling, deep down in the soul that defies any real explanation. The Shrine, in its concrete time and place, where we visit it, is a visible symbol of that untranslatable grace. Symbols are often universal and are used because they are not tied down by a specific language. Instead, they are bound within a cultural experience. If we are serious that Schoenstatt becomes way of life for us, then we participate in a common culture that is characterised by a specific spirituality and lifestyle. A Schoenstatt culture.

What a text from Father Kentenich in my language can mean

Similarly, our Covenant of Love has the structure of a contract, and is therefore necessarily bound by language. Throughout the many countries that we find ourselves in, we must translate the contents of the Covenant of Love made by the founding generation so that we too, may participate in that same Covenant. However, such a covenant is nothing new to the Juedo-Christian tradition, and as such, surpasses the constraints of language and again, is felt in the relationship of love between God and his people, both collectively and in the heart of each individual.

It is true, I often feel sad that I have so little access to the writings and thoughts of Fr. Kentenich and the content that is available to me in English is limited and sometimes awkward to read, due to the constraints of the English language in attempting to translate a complex and abundant language as German and I know that I cannot always identify with the person of Fr. Kentenich because I have not been exposed to as much of his life and thought as has a German speaker. Yet, I know that I cherish those few texts so tenderly because they are all that I have to reach out to and through them, discover the life and work of the founder and through these, the life of the Schoenstatt Movement.

In our modern world where we are surrounded by and have unlimited access to infinite texts covering every imaginable topic, I believe that we risk becoming a superficial generation. We simply do not have the time to read and to know everything, so we often content ourselves with the skimpiest skin of a plethora of subjects. In face of this, I look with wonder on the experience of the Kenyan Schoenstatt Family, to name only one of many such examples. Documents containing Fr. Kentenich’s writing are few and far between and access to technology to reproduce these not readily available. Subsequently, documents are painstakingly and lovingly copied out and then passed from hand to hand, laboriously studied, and passed on once again, until they are little more than ‘thread’-bare scraps of paper. These often travel many hundreds of kilometres and are awaited by expectant readers. Are these people not perhaps better acquainted with the life and the spirituality of our Founder, than many of us, who read sermon after sermon, letter after letter in an attempt to know him better? Simply because they have taken more time to soak up each word and meditate upon it? By extension then, could not their experience of Schoenstatt be far deeper than any of ours? Without ever having visited a Shrine or imagining what one might look like, is it not possible that some of those people know Schoenstatt better than I do?

Same spirituality, different experiences?

And yet, no experience of Schoenstatt could be more different: A German Schoenstatt Father living on Mt. Schoenstatt, a mother in a secluded rural village in Kenya, a young student in Milwaukee, a Schoenstatt family living in Santiago, Chile or me, a young South African woman living in Johannesburg, the most developed city on the African continent. Each of us has an entirely different story to tell about their life as members of the Schoenstatt Family. I cannot possibly conceive what it must be like for that mother in Kenya to raise her child and try to educate her children in the way our Blessed Mother educated her, nor can the family from Santiago, where Catholicism is the predominant religion and Schoenstatt is so vibrant and passionate, understand the smallness of my local Schoenstatt Family where less than 10% of the South African population is Catholic. To take this thought even a step further, even though Simon Donelly and I share many common experiences as South Africans, his experience of Schoenstatt as a young man growing up in Cape Town in the 1970s, I am certain, is very different from mine, growing up in Johannesburg in the 1990s, simply because the very essence of our country changed so dramatically; politically, culturally and economically; in those twenty years. Even within my own Schoenstatt group, many of the girls (now young women) studied together with me, but their experiences of Schoenstatt are unique, even though we shared many similar experiences. In our group alone, three of us have spent time in Schoenstatt, Germany in the last 3 years, but our lives in Schoenstatt, the people who shaped us during that time and the experiences that molded our faith as young women could not be more different. When we meet, we like to talk about these things that we shared, but yet there comes a point, where we can no longer find words that the others will understand to describe some of the things that we lived.

Therefore, in spite of the many things that we all hold in common and take as our centre, each of our individual experiences of Schoenstatt are very different that even in a common language cannot be translated from one person to the next. It is perhaps the untranslatability of Schoenstatt that has allowed for the graces of the Shrine, given to us by our Mother, to spread from country to country such that little less than a century after its founding, Schoenstatt has found itself to be a vibrant Movement within the Church and a powerful force in all walks of life on every continent. Each time that grace manifests itself, Schoenstatt "refounds" itself. Yes, Schoenstatt in each country has its particular flavour, each course has particular characteristics that make it unique, but each of us found Schoenstatt anew in our lives, in our homes, in our world.

The new man and the new society

Some very concerned voices may object and suggest that if we carry on in this vein, we may come to a point where our spirituality is not at all like Fr. Kentenich envisioned it. Yes, and no. Schoenstatt’s main aim as part of its mission to renew the Church is to educate the new man for a new society. However, society is ever-changing and subsequently, the nuances of Schoenstatt must change to keep abreast of our fast-changing, and ever more so, world so that it continues to be relevant to the people to which it reaches out. Yet, in this yes, there is also a no. The very core and the very essence of Schoenstatt cannot change – our Covenant with our Mother in which we agree to be her instruments and allow her to mould us and shape us cannot be forgotten.

As a final reflection on the mystery of Schoenstatt’s (un)translatability is my own personal experience of it. I deepened my love for Schoenstatt, and my relationship with our Blessed Mother during a period of nine months that I spent in Schoenstatt’s original places nearly two years ago. While there, I experienced and lived indescribable moments with many Spanish and Portuguese speakers, with whom I now find a closer bond than my own Young Women’s group in Johannesburg. Out of necessity, I learnt to speak Spanish and put my disused mother-tongue (portuguese) to good use so that I could express and absorb these experiences. Today, my most ardent conversations with Mother are very child-like and I can only achieve this if I pray in Spanish. I continue to share my thoughts and life as a Schoenstatter with dear friends (who have become more than brothers and sisters to me) mainly through the mediums of Portuguese and Spanish. So while English may be the language through which I interpret my world, I find them inadequate to express my Schoenstatt world. In that lies the very essence of the Schoenstatt mystery – although rooted and founded in a concrete time, place and tongue, Schoenstatt draws new life and flourishes by transcending all time, place and linguistic medium.