|

|

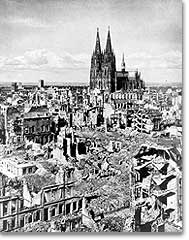

Alemania hace 60 años ... Germany, 60 years ago... Deutschland vor sechzig Jahren... Foto: Archiv © 2005 |

|

|

|

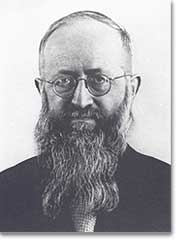

P. José Kentenich como prisionero en el campo de concentración Fr. Joseph Kentenich as prisoner in the concentration camp P. Josef Kentenich als Gefangener im KZ Dachau |

|

|

|

Mayo de 1945: el Padre Kentenich, liberado del campo de concentración, trata de volver a Schoenstatt May 1945: Father Kentenich, freed from the concentration

camp, is searching ways to return to Schoenstatt in post-war Mai 1945: Pater Kentenich, aus dem KZ Dachau entlassen, sucht nach Wegen, im Nachkriegsdeutschland nach Schönstatt zurückkehren zu können. |

|

VOICES OF TIME, Fr. Dr. Joachim Schmiedl. "I state my shame," said Federal Chancellor Gerhard Schröder on the commemorative event arranged for the anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz conentration camp. Sixty years after the end of the second world war, Germany, the nation that sparked unspeakable grief, is once again confronted with her past. The perspective changes a bit though, from the shame about the own actions to the perception of all the suffering during the end of the war.

The air raids on the German towns, the awful experiences of being in the expulsion from one’s native country, the experiences of captivity and the breakdown of Germany come back to memory and require commemoration and reflexion. The Federal Chancellor stated: "The overwhelming majority of Germans living today carry no responsabiltiy for the Holocaust. But Germany still carries a special responsibility." The German bishops also point out this responsibility in their writing for the occasion. They speak of the effects of "mechanisms of suppression" that are still present, and of the complicity of the "mere supporters and of all the others who ignored the facts".

Schoenstatt: a victim several times

If the Schoenstatt movement looks back at the time of National Socialism and of the Second World War, it does so in the consciousness that the movement on several occasions became a victim of Hitler's regime. The beatification of the priest Karl Leisner, who was ordained 60 years ago in the Dachau concentration camp, is felt as an ecclesiastical seal on this self evaluation. One can point to the women and men who had to suffer much in prisons and concentration camps, those who died in them or were killed out right. Names like Lotte Holubars, Franz Reinisch, Albert Eise and Heinrich König, but also survivors like Josef Fischer and Heinz Dresbach stand for a line in the opposition which was not a part of the loud protesting, instead quietly coping with the situtation that they where living in, guided by the belief in the mighty closeness of a loving, though demanding God. For them the guideline was the clear interpretation of the history by their founder, Fr. Joseph Kentenich.

However, it also is a matter of positioning oneself to the ambivalence of human existence. In the case of the Schoenstatt movement there is Ferdinand Duchene. In August, 1919 he was one of the participants in the foundation conference of the Apostolic Federation in Dortmund Hörde. In the late 1930s he left the Pallottines and gave up his priesthood. He became an employee in Heinrich Himmler's National Security Head Office, where he was occasionally active in the church department. Till the present it is an isolated case in the sphere of the Schoenstatt movement.

"I withdraw from where I would have to fight "

In a course of lectures at the end of April, 1946, Fr. Kentenich concerned himself with the concept of a German collective guilt, ventilated today and at that time. The concept itself seemes from a theological perspective ill chosen, because guilt assumes an internal personal approval and "collective " suggest the absence of this personality that has the possibility of free will. Still, Kentenich argued thoughtfully: "Nevertheless I believe, that many people would have to beat their brest " (Religion-educational talks in Rottenmünster (from the April 29th to May1st, 1946), in: Josef Kentenich,: Das katholische Menschenbild.. Worked on by Herta Schlosser, Vallendar in 1997, 155.)

He pointed to the partial responsibility of the Germans who would have brought Hitler to power by choice. False hopes have been woken up by the conclusion of the Reichskonkordat (the treaty between church and state), the mark of diplomatic politeness among the general public has been misunderstood. In this direction guilt also pointed to everyday behavior: "I withdraw from where I would have had to fight. […] We have been apart from other people, we have supported the wrong currents or have not fought against them."

Many reasons are made known for this behavior, which can be judged in a superior manner or with humility and shame. The determining question of the future still exist and nevertheless, remains, after the internal coping has happened. The German bishops point to persons who have in a scientific (Victor Frankl) or poetic form (Elie Wiesel, Paul Celan, Primo Levi, Imre Kertesz, Louis Begley) offered to the postborn a "looking into the depths of human existence and at the same time opened to the possibilities of dispute".

God of history, God of mercy

Much support for coping is found in Fr. Kentenich. He puts the historical facts in the context of a historical-theological interpretation. With the reference to John’s Apocalypse, Fr. Kentenich understands history as a part of a final battle between good and evil. The person is a player, his role is determined according to his decision for or against the good God. Kentenich was never ready to take away any of the seriousness and the consequences of free will. Therefore, he also took into consideration the possibility of failure - for individuals and for peoples as a whole. However, apocalyptic scenarios for Kentenich always stood in the larger context of the theology of grace. Jesus commpassion with the hungry people (Mk 8:2) was for him a guideline for how to react to human and social breakdown. The sense of apparently incomprehensible events, human sin and sinful structures, with Paul he saw it in "For God delivered all to disobedience, that he might have mercy upon all. " (Romans 11:32).

Beyond all efforts towards understanding the unconceivable and trying to explain human failure and personal and political guilt, the social breakdown that reached it’s climax 60 years ago can be an invitation to discover the religious perspective anew – so that God may also take pity on his people today.

With friendly approval of the author and the editorial staff, taken from: Regnum. Schoenstatt International - reflection and dialog, Patris publishing company Vallendar-Schoenstatt, 1, in 2005, p. 1f.

Translation: Kelsie Bias, USA