GERMANY, MSGR. Dr. Peter Wolf •

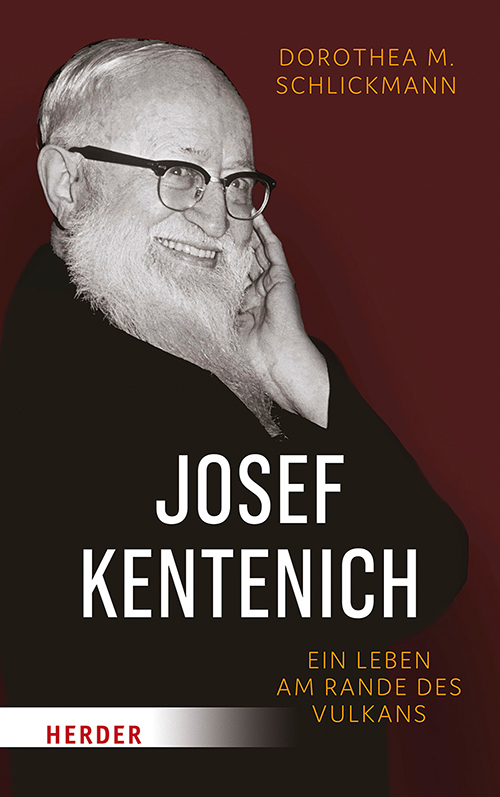

The new biography of the founder of the Schoenstatt Movement by Dorothea Schlickmann has a surprising subtitle (A Life on the Edge of a Volcano). In the course of reading the biography it proves to hit the nail on the head. The graduate author who has published profound research on Schoenstatt’s founding period, here presents us with a highly informative biography of Fr Kentenich. She calls it a “narrative biography”. It is easy to read because it does without footnotes. At the same time the author assures the reader that the narrative portions are closely based on historical documents. Original quotations of Joseph Kentenich’s words are always highlighted.—

Many documented memories show the light and shadow sides of his childhood. Mention is often made of his illegitimate birth and its painful consequences. Young Kentenich was not even spared a time in an orphanage. A fictional letter from his mother relates what happened in the Oberhausen orphanage before the statue of Mary, and cautiously explains what the “consecration of the nine-year-old to Mary” would mean for the rest of his life. Josef wanted to be a priest, which was impossible at that time for an illegitimate child. Through Fr Savel a way opened for him to be educated by the Pallottine Fathers as a missionary in Africa. This was how the young Kentenich arrived in Ehrenbreitstein.

Youthful struggles

The start of the Novitiate in Limburg intensified the situation for the nineteen-year-old. There followed a period of “youthful struggles” that led him to the edge of the abyss in the fullest sense. This was immediately followed by a life-threatening tuberculosis. With the start of his studies for the priesthood the highly gifted student was drawn into the controversies of modern philosophy. Fundamentally it was a question of the truth. He wanted to take a stand to the discussions and also read the works of Kant and Nietzsche, which were on the Index of books forbidden by Rome. This led to serious inner conflicts. As his studies came to an end his admission to perpetual vows almost came to grief because of the opinion of one of his professors. Fundamentally, for Joseph Kentenich the faith was always connected to risk.

On 8 July Joseph Kentenich was ordained to the priesthood in Limburg, and a further year of studies followed. After completing his studies with brilliant marks he was sent to Ehrenbreitstein to be the teacher of Latin and German. This became a time when he took his first steps as an educator and developed a new way of working with the students on the basis of complete trust. Then followed a time as Spiritual Director in Schoenstatt with the start of a new foundation. The account draws on the rich knowledge of the author.

Confronting madness

The next chapter brings us to the Nazi period. Kentenich recognised the dangers of this ideology and sought to influence groups of priests and laity in the educational field to place the emphasis differently. The biography mentions the actual numbers of those attending his courses for priests, and his pedagogical courses for the laity and religious, all over Germany and Switzerland. Until now no one has been aware of the size of these groups. The history of Franz Reinisch, the only priest who refused to take the military oath of allegiance to Hitler during the Third Reich, and who was condemned to death as a result, bears the heading: “Confronting madness”. Fr Kentenich was the only one who confirmed him in his conscientious decision and accompanied him spiritually. In September 1941 Kentenich was arrested, and this led to his “imprisonment in the dark” in the Gestapo prison in Koblenz. After four weeks he was released unbroken, and transferred to the nearby prison in the Karmeliterstrasse. There the decision was taken to transfer him to Dachau.

The author manages to describe the actual conditions in the concentration camp at Dachau in a few words. She also describes the goals of the SS and the consequences of the various measures among the prisoners. The biography attempts to describe Joseph Kentenich’s way of dealing with these inhuman conditions. She discusses his decision to take up letter contact with outside, which was forbidden, and how he dictated whole books in verse form. In this way he tried to guide his foundation from a distance. Other prisoners quite understandably objected out of fear of the consequences.

After he was released from the concentration camp he made his way back to Schoenstatt, where he received a warm welcome on 20 May 1945. However, he had not come to take a rest and to celebrate his release. He had big plans. He saw the great task of helping Germany to digest and work through its great burden of guilt. He was also busy completing the foundation of his communities, such as the institute for Diocesan Priests and the women’s Institute of our Lady of Schoenstatt. I also greatly respect the honesty with which internal difficulties are also mentioned in this book. It helps us to understand developments better and guarantees the faithfulness of this biography to history.

Visitation and exile

Two dense chapters follow on the tensions with Church authorities and Fr Kentenich’s exile. In many instances Dorothea Schlickmann calls a spade a spade. Josef Kentenich did not duck the controversy. He wanted the Bishop of Trier and the German Bishops’ Conference to study Schoenstatt. He did everything he could to have a “study commission” set up. However, instead of a “visit”, it became a ‘Visitation” with all that that implied of suspicions. The closing address by the Visitator confirmed, first of all, that Schoenstatt was a work of God and was in agreement with the teaching of the Church. Its practice, however, he said, gave rise to shortcomings and dangers. Two months later a letter from the Auxiliary Bishop arrived which upheld the judgement that Schoenstatt corresponded dogmatically with the Church, but mentioned considerable objections in the pedagogical field. He criticised the Sisters of Mary harshly, as well as some collaborators and the founder himself. This forced the founder to act. He began a detailed answer, the so-called “Epistola perlonga” – very long letter.

In the following pages of the biography, the author enlarges on the further steps that led to the Apostolic Visitation, which Auxiliary Bishop Stein obtained through the Congregation for Religious in Rome. This gave rise to the intervention of the Holy Office. Professor Sebastian Tromp SJ was appointed Visitator. A follow-up discussion showed that the aim was to separate Fr Kentenich from Schoenstatt and his foundation. The Holy Office insisted that he would have to lay down all his offices voluntarily, otherwise he would only return to Europe in a coffin. His answer: Voluntarily, never! If he was sent, immediately! The biography describes the bitter and dark situation and its human hopelessness.

Fourteen years of exile followed. We are told a great deal about the time he spent in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, and the difficult situation of Schoenstatt in Germany. We are told about plans ready for signature to disband the Sisters of Mary. The biography describes openly the ever-new accusations and denunciations of the founder. In the end the exile became a time in which many got to know him as the pastor of the German parish, without knowing anything about the history of the Visitation. He was heart and soul a pastor. Then came the turning-point through the Second Vatican Council. The Holy See ordered that Schoenstatt should become an independent body.

“Return Home”

The final chapter is entitled “Return Home”. It summarises the return of the founder from Milwaukee and his death. A telegram, the origin of which has still today not been fully explained, summoned the founder to Rome. However, no one there knew who had sent the telegram. It critically endangered all the efforts to bring about the founder’s return home. Yet then the Vatican decided that he need not return to Milwaukee and his case was handed from the Holy Office to the Congregation for Religious. With that all the decrees of the Holy Office were rescinded. On 24 December 1965 the founder returned to Schoenstatt.

Three years followed that were brim full of work for his foundation. He used the time for countless encounters and the completion of the foundation of the Movement. He died on 15 September 1968 after his first Holy Mass in the newly completed Adoration Church. He is buried where he died. The words DILEXIT ECCELSIAM mark his tomb. The biography reveals that it wasn’t made easy for him to love the Church.

ISBN: 978-3-451-38388-5

Original: German, 03.02.2019. Translation: Mary Cole, Manchester, UK