GERMANY, Maria Fischer •

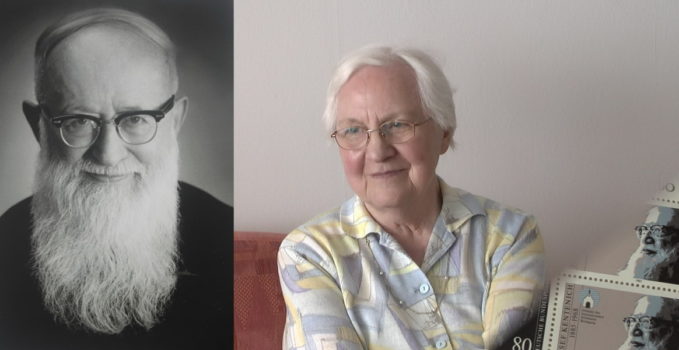

It was a sunny and warm afternoon in July of 2012, in the center of Stuttgart, in Theresia Zehnder’s well-lit and smartly furnished apartment. Already an octogenarian, only recently she had worked as a photographer in her studio “Hostrup.” She had coffee and sweets on the table while the camera and microphone were being set up. A perfect professional: “Will my photo picture be OK?” she asked me, “I do not want it to be a simple snapshot!” Oh, Oh, Oh…

She had taken photos of all kinds of people: bishops, artists and politicians, also St. Mother Teresa and the Founder of the Schoenstatt Movement, Father Joseph Kentenich. And she feels proud that these photos of Father are the only ones done professionally. Snapshot or picture. We were in the middle of the topic before the camera began to record.

The idea of this interview emerged during an encounter of the International Kentenich Academy for Directors IKAF (abbreviation by initials in German: Internationale Kentenich-Akademie fur Fuhrungskrafte). What did Father Kentenich give to this professional woman for her entire life, a woman who was always independent and had established the highest quality standards of her profession? And how did she find her way in Schoenstatt and how did it form her life? This interview was never used within the IKAF. It is now priceless. Theresia Zehnder died Friday, September 2nd, at the age of 87.

The way to Schoenstatt: “beyond the parish, toward other dioceses and other countries”

Theresia grew up in a religious environment. “My mother was very religious. We went to the parish everyday. The region of Schwabisch Gmund is very Catholic! But that did not harm us,” she said smiling. They were six children, three boys and three girls, with 20 years’ difference between the oldest and the youngest. In the parish, she was very efficient, collaborating in the preparation for Holy Mass. “We had a leader who belonged to the Secular Institute of Our Lady of Schoenstatt. She led us from youths in the parish to the Schoenstatt Youth. That was in the beginning, just after the Second World War!” What interested you in Schoenstatt? “It was something that went beyond the parish, toward other dioceses and other countries.” International, broad, diverse. That is what attracted Theresia.

In 1950, she had a profound experience with Father Kentenich. During wartime, the image of the “Marian Garden (Mariengarten)” emerged to describe the process of becoming mutually responsible and in solidarity with the Covenant of Love, fidelity and mutual commitment, inclusively beyond pain: a covenant between the Father and Founder and his family that moved the members of this family to become radically responsible for each other becoming allies. Father Kentenich incorporated the members of the Girls’ Youth into this process, and they decided to incorporate themselves into this covenant life. Theresia Zehnder was present during this event in Schoenstatt in 1950: “We went to the sacristy, and I still remember that our leader was present.

She said: ‘Father, may we shake your hand?’ And he answered: ‘I want you to give me both of your hands.’ For us, this interesting situation was very normal: Father was simply Father! We had not registered that he was a great man, such an important personality. The Sisters of Mary appeared eager around him, but for us, this priest who had founded Schoenstatt was someone completely normal.”

It was my all

Theresia was diocesan leader of the Schoenstatt Youth, she intensely lived the conferences with Fr. Bezler in the Schwarzhorn (a mountain in the Alps, in Tirol) and felt profoundly motivated: “Above, in the Schwarzhorn, we buried things, and we had conferences. During one Holy Week, we walked up the Schwarzhorn three times, a three and one half hour hike. We would all sleep in the great dormitory, and we would bathe in the great bathroom. Everything was so obvious. Father Bezler taught us to eat slowly, that way the last one could also finish eating with everyone else. All these small things meant being family for us. At home they soon told me: Well, take your bed, that way you can spend all your time at the Schwarzhorn. Schoenstatt was everything for me…”

She decided to enter the Schoenstatt Women’s Federation. Theresia responded to a question that had never been asked of her before: “I did not want to be a Sister of Mary. That option seemed very narrow to me, much too narrow for me. And I would not have been able to work anymore in my profession.” In Schoenstatt you find the broadness of apostolic vocations: apostolate alongside the profession, apostolate in the profession, and at the service of everyone who opts for one or a mixture of these options, and the apostolate as a profession also exists. Theresia Zehnder was a photographer in body and soul. And her profession became her apostolate. What fascinated you about the Women’s Federation? Her answer was only one word: “freedom.”

“My creed always was: each person only exists once. If I am able to discover this singularity in my photographs, then it is a good photo. I have to dedicate myself to the person, discover his/her personality. I had a photography studio. We never made technical photos. I always prayed the consecration prayer for each client for thirty years, because I told myself: I have to discover what the person represents. The majority liked their photos and, of course, there were also many who did not feel the same, because they saw themselves differently.”

And in a very simple way: “While I am taking photos, I cannot talk to my clients about Schoenstatt. But if I am able to transmit it to someone who is unique, then that is pure Schoenstatt.”

How can that be done professionally?

“I never said: ‘smile!’ I only said: ‘think of something beautiful!’ That is the difference. One can smile with the eyes or the mouth that is the difference. Sometimes someone said: ‘Oh, there is nothing beautiful for me.’ The most difficult clients were those who rejected themselves. They were truly difficult.”

“For example, if I had as a client a forest ranger who came with his green jacket, he felt good. The same happened with a doctor who felt more comfortable with his white coat. It is about seeing and photographing the people in the context to which they belong. I photographed many bishops. It was much easier to photograph the bishops who were themselves and not those who wanted to stress their position. And many of them I photographed several times. Yes, I photographed many bishops. On one occasion, Bishop Georg Moser, Bishop of Rottenburg Stuttgart, called me and asked me: ‘Do you want to photograph Mother Teresa?’ He asked me to go to the Marienhospital and told me: ‘Come tomorrow at breakfast, you will be able to do it there. Truthfully it was he who wanted to have photos taken alongside Mother Teresa. The photos were taken on the balcony, in open air. Mother Teresa was very natural, she gave no importance to herself.”

Studio Manager with the picture of the shrine in her studio

“I always had a photo of the shrine in the studio. And a large one! And it happened more than once that someone said: ‘Oh… do you belong to that place?’ ”

As a young woman in the 1950’s, how did you get the idea of becoming a studio manager?

“For a time I worked in Leverkusen and also in Mainz. But I did not like that. I returned to Stuttgart and completed my Master’s Degree in photography. Usually you work independently, that is part of the profession. Things simply developed: the owner of the Hostrup Studio, where I was an employee, wanted to retire and there the topic surfaced: ‘who will manage the studio?’ I was lucky: my family had just sold a house and I received part of the inheritance in cash. It was precisely the sum I needed to buy the studio.”

Did Father Kentenich say something to you as a studio manager?

Yes, he did, and Theresia Zehnder still remembers it perfectly. It was after a series of photos that she had taken of the Founder when it was possible to talk to him.

“Dear God, what am I going to talk to Father about? I don’t know him very well,” that was her first reaction. “I thought: surely he will ask me about my course ideal and about other Federation topics.

Instead of that, he asked her:

‘How much does your business cost and how did you pay for it?’ And then: ‘if you need money, do not ask your relatives, friends or family, go to the bank. You pay interest there, but you are free.’”

From the exile in Milwaukee, Father wrote her a letter regarding the buying of the photography studio: “A cordial greeting and blessing for the purchase and the new responsibility with the business. A true daughter of Schoenstatt should dare something.”

When Theresia spoke with him years later about the challenge of being a leader to her former colleagues, he gave her the following advice: “Somehow you must remain very childlike, then it will work out well. Then one is sufficiently strong to be a leader for others. A certain distance exists when one is a leader. In some place, you will have to be at home, but in another place.”

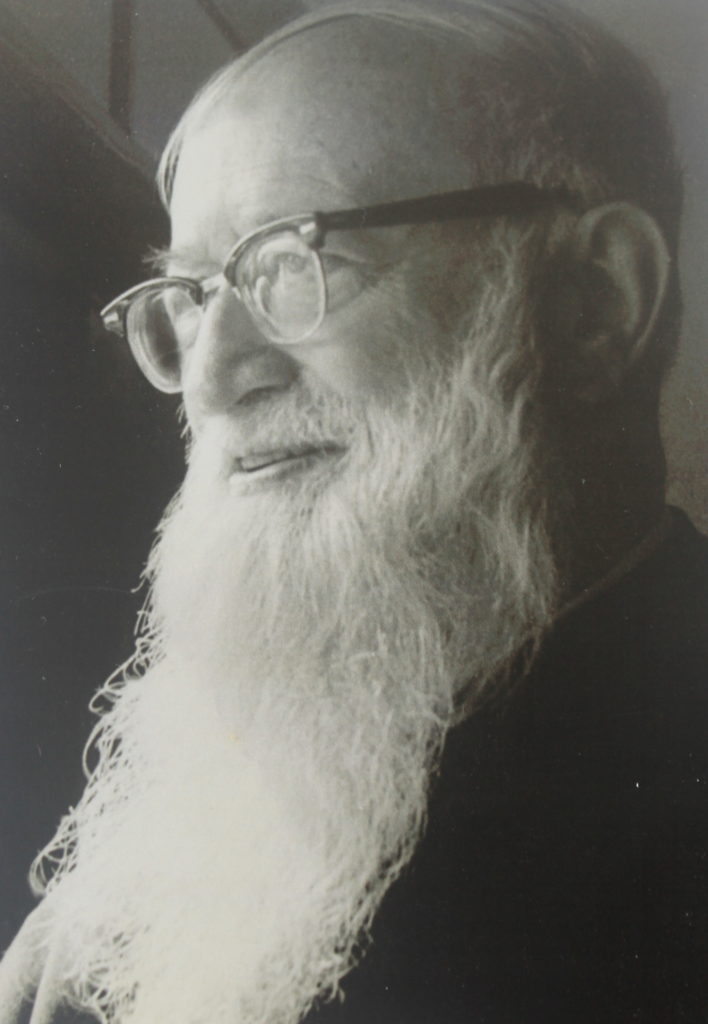

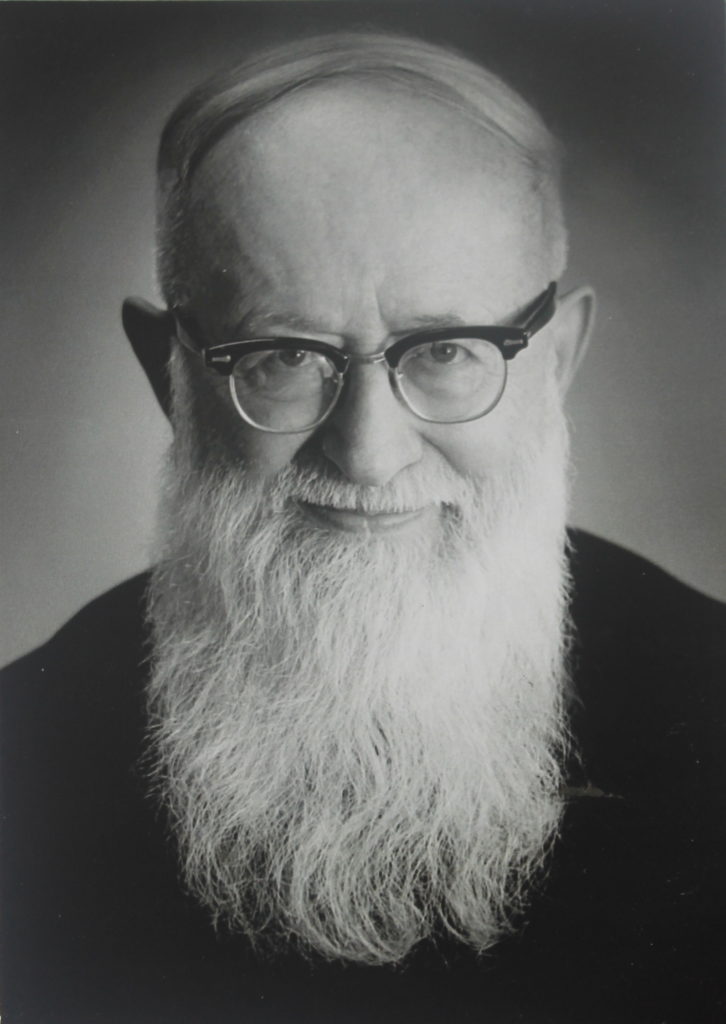

The “image of the prophet”

We approach the topic for which Theresia Zehnder is well known in all of Schoenstatt. How was it possible that you would take that very familiar and beautiful picture of Father Kentenich?

“It was Sister M. Zita’s ‘fault,’ ” clarified Theresia Zehnder. “She had taken many photos of Father Kentenich, but I told her: ‘what you have done is marvelous, but they are only snapshots. I do not want only snapshots. But the other Sisters did not consider this to be the case. On the contrary, they would have taken Father to my studio when he was in Stuttgart, which was only fifteen minutes from the station. At the station, I took various photos and made a video. There I also took the photo that was chosen for the stamp in 1985. That is truly my favorite photo of Father Kentenich because there he appears as the prophet.”

During these takes in Stuttgart “we agreed that I would take some studio photos. This time, something done very well!” Father Kentenich was in agreement.

And without expecting the question, he said: “There are so many photos of him! In some you can barely see the white beard, and all think that it is fantastic, but that is all. That cannot be. Father Kentenich is much more than a white beard.”

The pictures in Wurzburg

The moment came at the Schoenstatt Center in Marienhohe, in Wurzburg. The pictures of Father Kentenich were taken there. Theresia Zehnder remembered each detail:

“When I learned that Father Kentenich had the barber come the day before, I felt more tranquil. I thought: he is taking it seriously.

I took all the things I needed: I arrived by train with the great tripod and camera! And at the same time I thought: my Master’s examination was easier than this.

Then I told him: “Father, I want a timeless image!” Therefore I photographed him without a smile. I do not like it when there is an image with a smile that is not timeless. “For the photo, I needed a white wall, a table and chair, nothing more. Father Kentenich, she related, “sat in the chair and asked: ‘am I alright now?’ ” And he passed his hand over the length of his beard from left to right. “Father, you are always beautiful” – ‘no, sometimes something stands on the top of my head.’ ”

The Sisters were standing next to the door, observing. I could not work this way, in spite of my good intentions. Then I asked the Sisters to leave. Father enjoyed the situation immensely, the way I had dealt with the Sisters. But I told him: “I cannot work with a group of people behind me, observing.”

Everything was ready in a half hour. I took twelve rolls of film with the camera. I used a new roll for each take. Eight to ten photos were made. I was very afraid. I thought, if something goes wrong, I wouldn’t be able to ask him to pose for new photos! I then gave him the developed pictures.

Theresia Zehnder had one last personal encounter with the Father and Founder. And this encounter was also something typical: “After a chat, he asked me to come close and he asked: ‘Did someone pay you for the photos?’ Naturally, nobody had thought about this, so I answered: “Father that should not be a problem for you. I am happy to have taken these photos.”

And after a moment’s reflection, he added: “That half hour with the photos was the culminating point in my life.”

Original German: Translation: Carlos Cantú, La Feria, Texas USA. Edited: Melissa Peña-Janknegt, Elgin, TX USA